In no other area of family law are battered women and their children inadvertently subjected to greater physical and emotional harm than in the child custody andvisitation context. Battered women are often forced to participate in custody arrangements that requiremediation, unsupervised custody and visitation, and

other types of exchanges that leave them and their children vulnerable to continued abuse and control at

the hands of their batterers. Women who try to protect themselves and their children by seeking sole custody or modifications in custody arrangements such as cessation of visitation, supervised visits, or who flee with their children are penalized by having custody taken away and given to their batterers. Despite the perception that mothers always win custody, when fathers contest custody, they win sole or joint custody in 40% to 70% of the cases. Indeed, even in cases where abuse is reported, a batterer is twice as likely to win custody over a non-abusive parent than in cases where no abuse is reported.

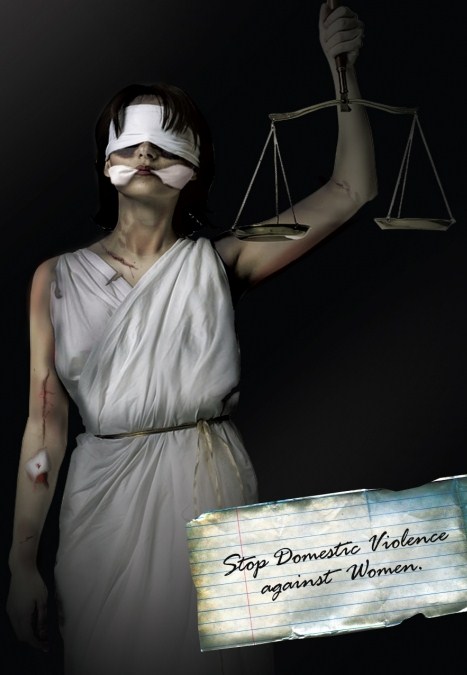

Domestic violence

While there is no uniform law that governs child custody, all states use the same standard in determining custody arrangements, called the “best interest of the child” standard. Under that standard, courts look at a number of factors in determining what type of custody arrangement would best suit the child’s physical, intellectual, moral, and spiritual needs. Most states have separate statutes governing child custody and domestic violence. Although many states require the court to consider domestic violence in making temporary or final custody determinations, others do not. Moreover, a number of state custody

statutes make no mention of domestic violence as a factor to be considered in making custody awards. Of equal concern are joint custody provisions that do not take into account how domestic violence puts both the

survivor and her child/children at further risk. See the section of this Legal Resource Kit entitled

“State Custody Laws That Consider Domestic Violence” for a complete list of custody statutes in the different states. Indeed, for the battered woman, the custody and visitation processes often become a means by which a batterer furthers his abuse through attempts to continue to maintain control. Most forms of shared custody and visitation involve some type of proximity or contact between the battered woman and her abuser during the exchange of the child between parents. During these exchanges battered women are often subjected to verbal and physical harassment, stalking, assault, and threats,including the threat of child kidnapping.4 Women who deny visitation or who go to court to request a modification or supervised visitation in order to protect themselves and their children are frequently accused of trying to alienate the

child from the abusive parent.

III. Myths and Facts About Domestic Violence and Child Custody

The unfair treatment of battered women in custody disputes results from myths about the impact of domestic violence on women and children, as well as the widespread failures of civil protection agencies in taking women’s experiences seriously. Here are some of the common myths that persist:

Myth: It is easy for a battered woman to leave her abuser or to stop the abuse.

Fact: Fear of losing her children, pressures from religious communities to stay in the relationship, financial

dependence, the insensitivity and unresponsiveness of the justice system, and the escalation of abuse that occurs when women try to leave make it difficult for a woman to separate from her abuser. Even when a battered woman appears to “just accept” the violence, she is often making different attempts to avoid and stop the violence. Such attempts include complying with (or anticipating) a batterer’s demands, demanding that the batterer stop hisabuse, orchestrating the environment (e.g., keeping children quiet), leaving the home, calling the police, and fighting back with or without weapons.5

Myth: Battered women who take their children and flee an abusive relationship are safe from further harm.

Fact: Studies find that domestic violence escalates when battered women leave their abusers, and that terminating a relationship results in a greater risk of fatality for battered women and their children.6 This

abuse takes the form of threats and actual violence to the mother and her children. Further, women and their

children risk additional (and sometimes fatal) harm during court ordered visitation or joint custody

arrangements. This occurs as many batterers discover that the children are a means of continuing the abuse of

a former partner. Five percent of abusive fathers threaten to kill their children's mother during visitation

with their children and 25 percent of abusive fathers threaten to harm their children during visitation.7

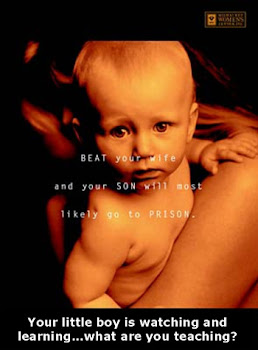

Myth: Domestic violence between parents does not impact their children.

Fact: While most mothers in abusive relationships take precautions to shield their children from the harmful effects of violence, it is extremely difficult for them to protect their children from witnessing or experiencing abuse. It is estimated that 87% of children who come from homes plagued by domestic violence actually witness the abuse.8 Most children are adversely impacted by the abuse, although how they are affected

may vary. Research suggests that child witnesses of domestic violence are more likely than other children to

feel helpless, fearful, depressed, and anxious. They suffer both emotional and physical developmental

problems, and are more likely than children who do not grow up in homes plagued by domestic violence to

suffer from anxiety, low self-esteem, and depression.9 Many experts believe that child witnesses of domestic

violence internalize the fear and trauma that results from witnessing violence, and are themselves likely to

become perpetrators of violence in the future.10

Myth: Abuse of one parent by another parent does not mean that the abuser poses any harm or danger to the children.

Fact: While research results vary, studies have found that child abuse occurs in 25% to 70% of the families that experience domestic violence.11 Further evidence linking domestic violence to the heightened risk of harm to children can be found in a report to the Florida Governor’s

Task Force on Domestic and Sexual Violence, which identified over 300 domestic violence fatalities in 1994; 73 of those victims were children. Most of the children were killed by their biological fathers. In some cases, male abusers killed their entire families, including themselves.12

Myth: Batterers who seek custody do so out of love for their children and a desire to be good parents.

Fact: Abusive fathers continue to abuse and exert control over women after separation by vigorously pursuing custody of the couple’s children.13 Batterers are twice as likely as non-physically abusive fathers to seek sole custody of their children,14 and frequently refuse to pay child support as a way to continue the financial abuse and dependence of the mother.15

Myth: Battered women raise the issue of abuse in an attempt to turn their children against the other parent in order to gain sole or primary custody.

Fact: This allegation is often leveled at women who are simply trying to make judges aware of separation violence, their children’s concerns, and other abuses by the batterer. These assertions may be in the form of so-called “syndromes” like “Parental Alienation Syndrome” (PAS) or “Divorced Mother Syndrome.”16 Regrettably, however, judges, guardians ad litem, and court-appointed custody evaluators often rely on these theories to discount the very real fears and concerns that battered women and their children bring before the court.17See the section in this Legal Resource Kit on the “A Guide to Parental Alienation Syndrome” for information on how to address these assertions

(212) 226-1066

Sunday, June 13, 2010

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Children Learn What They Live

No comments:

Post a Comment